Saving energy with a cutting-edge cooker ventilation system

When you’re building a seafaring vessel, energy management is critical. At sea, every watt counts — and this becomes even more pressing when designing a world-first yacht that runs entirely on renewable energy, like Sailing Yacht Zero.

Without the safety net of fossil fuels, energy must be harvested from the environment, stored carefully, and delivered with precision. In this situation, a key element to be focused on is where the most power is being used. On sailing yachts, one big area is air conditioning — and this is often at its peak in the galley.

The team behind Sailing Yacht Zero recognized this as a major challenge and set out to design a completely new cooker ventilation system. What they developed could reshape how cooking units are built on land and sea alike.

To find out more, we sat down with Mark Robaard, a project engineer on Sailing Yacht Zero, to discuss this cutting-edge project.

The Challenge: Heat, humidity, and energy loss

“The galley requires a strong ventilation and air conditioning system on board, primarily due to cooking activities that generate a lot of heat and moisture,” says Robaard.

Cooking produces hot, humid air that must be extracted and replaced with fresh air. But when conditioned air mixes with cooking fumes, it becomes unusable, and the system has to work harder to re-cool and dehumidify replacement air.

“Since the boat will often be sailing through hot areas, the air coming from outside will already be warm and humid and will need to be re-conditioned, requiring more energy consumption,” Robaard says.

Removing water vapor requires orders of magnitude more energy than changing temperature. Every unnecessary liter of evaporated steam directly drives up energy costs.

Removing 1 kg of water vapor requires approx. 2,500 kJ (≈0.7 kWh), which is an order of magnitude higher than heating 1 kg of dry air by 10 °C (≈0.01 kWh). Thus, minimizing the required replacement airflow directly reduces energy demand.

Traditionally, open extraction systems use high negative pressure to capture cooking fumes. But this also draws in “false air” from the room, increasing replacement needs and creating a vicious cycle of wasted energy.

The goal of the Sailing Yacht Zero team was to improve the efficiency of the system and save energy by stopping the air from cooking mixing with the conditioned air. This was the task Robaard was given.

Trials and tribulations: Finding the right airflow

“We started with a simple question: how can we efficiently guide air on the cooktop to the extractor?” Mark says.

Rather than allowing the warm and humid air from the cooker to mix with the conditioned air in the rest of the galley, the team quickly decided that the best way forward was to extract the smallest amount of air as possible.

“The first idea was putting a smaller extraction hood or hoses directly on top of the pan,” says Robaard. Unfortunately, this proved impractical for chefs in a moving galley.

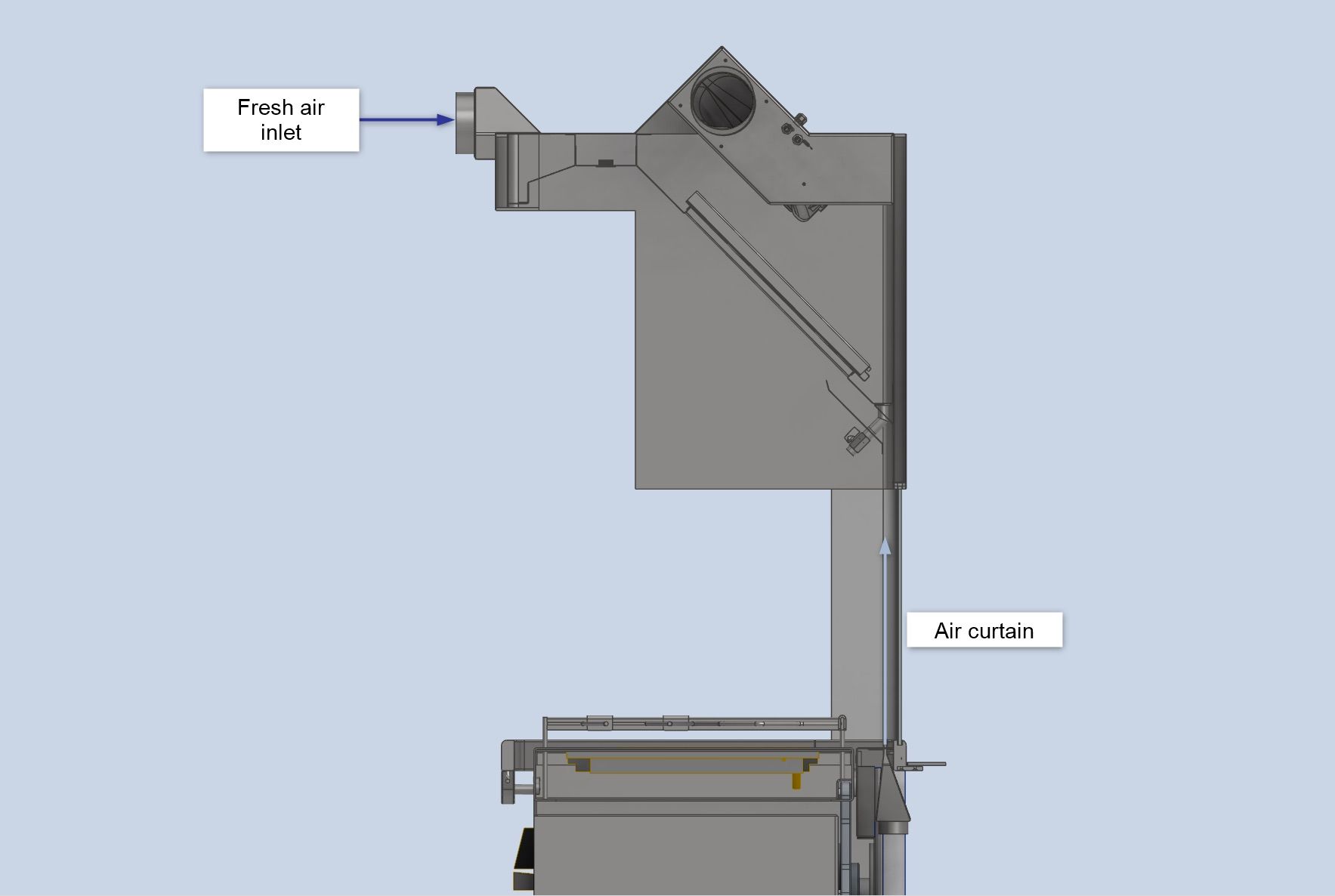

Next came the idea of an air curtain. “When you walk into a supermarket and there’s a wall of warm or cold air, that’s an air curtain,” says Robaard. In shops, this is to stop conditioned air escaping out of the door, and the team believed this principle could also work on a cooker.

The principle was sound, but early versions created turbulence and entrainment, pulling in conditioned air instead of isolating cooking fumes.

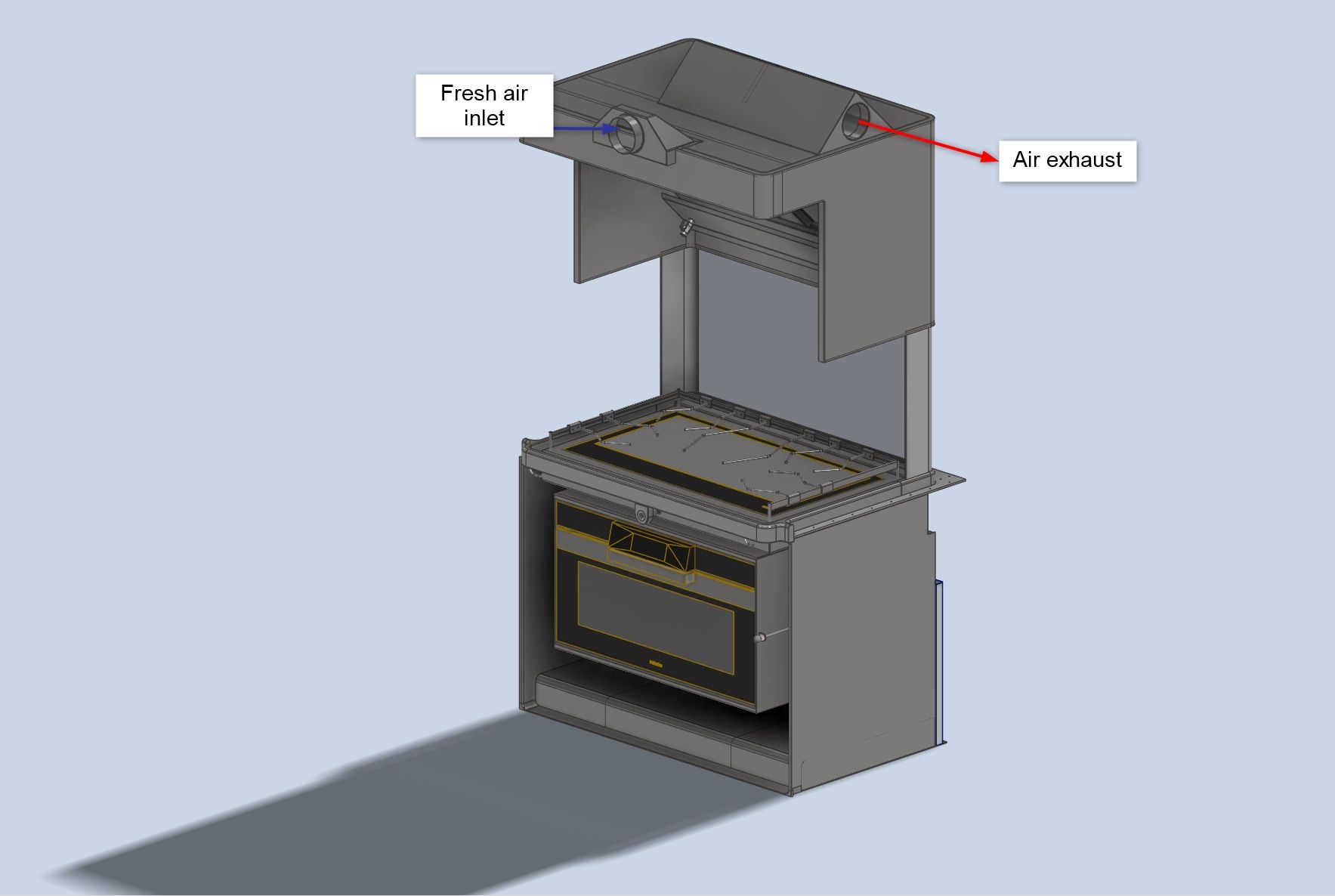

The breakthrough came with a hybrid approach that harnessed two physical principles: the venturi effect and the Coandă effect. These were used in the design of the over ventilation system in the following manners below.

- The Venturi effect: Air blown along a rear glass panel creates a low-pressure zone that entrains fumes directly into the extraction system.

- The Coandă effect: Airflow “sticks” to a glass surface, guiding vapors upward and preventing them from spreading into the room.

By closing off the back and sides of the cooktop while leaving the front open for accessibility, the system captures fumes efficiently while maintaining usability. Tests showed up to 50 % reduction in airflow volume compared with conventional hoods — meaning less conditioned air needs to be supplied, and fan power drops dramatically.

Smarter Cooking: Sensors and Slow Boiling

Airflow design alone wasn’t enough. User behavior can undermine efficiency: many cooks leave pots boiling unnecessarily, wasting heat and generating excessive steam.

To address this, Project Zero integrated sensor-controlled cooking technology. Smart sensors adjust ventilation in real time based on the measured air conditions above the hob, increasing extraction when emissions rise and reducing it when they ease.

The results

When it comes to energy balance, the proof is in the metaphorical pudding — and the positive results from this new oven ventilation system are stark:

| Component | Conventional model | Project Zero | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction airflow | 100 % | ~50 % | ~50 % |

| Supply air conditioning (latent) | High | Much lower | Major |

| Fan power | 100 % | 20–30 % | 70–80 % |

| Total energy demand | 100 % | 30–40 % | 60–70 % |

The future: A wider release

“This is a new approach,” Robaard says. “We haven’t found anything like this on the market before.”

While the ventilation system is still being built and installed, the team is dedicated to making the learnings they have gained available to anyone, meaning there’s wide potential for this technology to be installed in other environments.

“It can be used anywhere, basically,” Robaard says. Although it may require a slightly larger installation footprint — including an extra air supply for the air curtain — it’s something that could be a great energy saver in buildings across the world, especially in warmer climates that use air conditioning.

With system-level savings of up to 70 % compared to conventional models, this oven ventilation system is a prime example of how applied physics can be combined with practical designs to shift an entire industry.

This in many ways sums up the mission of Sailing Yacht Zero. By testing out equipment and advances in the adverse environment of the ocean, they can be refined and brought back to land and make a real difference.

Seafaring is a tough environment, and if technology can thrive on the water, it can do so on land as well.